Joe Bakhmoutski manages Simplify Cancer, a site, book and podcast with practical information for people with cancer.

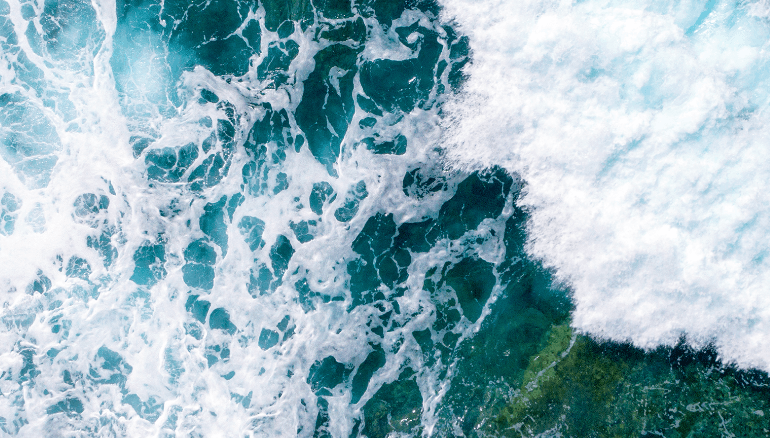

He draws on his own experience of having testicular cancer to help others steer their way through the choppy waters of cancer diagnosis, treatment and recovery.

He shares several tips on how he navigated cancer diagnosis and treatment below. Read Joe’s story.

Prepare for your appointments

I remember my initial appointment with the urologist who told me I had cancer. When he broke the news, I went completely blank, and could hardly take anything in.

Later, when I was preparing to have chemo, I would often walk out of an oncology appointment, and think, ‘’I should have asked about that…”.

In medical consultations, a high percentage of information is forgotten by patients, particularly when receiving bad news.

When going to your appointments, it helps to come prepared with a list of questions. This is especially important when you are meeting with specialists to plan treatment.

Ask if you can record the session so that you can listen to it later. I’ve spoken to a lot of specialists and most don’t have a problem with this.

It’s also invaluable to bring a support person along with you so that you can cross-check what the specialist said later.

I often found that when my wife came to appointments with me, she heard and remembered things differently to me because she was able to be a bit more objective.

Get the information you need to help you make decisions

I drew on the expertise of my medical team to get treatment information. I also spoke to people who had had the same cancer as me through online forums.

I tried to get a range of perspectives and asked lots of questions, particularly if I felt that information was confusing or one-sided.

I wanted clarity on what was happening, and often had to ask for simple explanations when specialists started using very technical terms — I would say, “can you please explain that to me again? I don’t understand”.

Sometimes, I felt like I was being a nuisance doing this but I felt it was important that I understood everything that was going to happen to me.

When I wasn’t sure about the answers I was getting from my specialist, I would get a second opinion, do my own research, and talk to people who were close to me to help clarify things.

I found voicing any concerns I had really helped me get perspective and make the decisions that were right for me.

Everyone who gives you information is sharing their perspective. No matter where the information comes from, you need to put it through your own filters and consider what is right for you.

Talk to other men

I wanted to talk to people who have been through what I was going through. While I went through both public and private medical systems, no one thought to give me contacts for support groups and other supports during or after treatment — perhaps they felt there was no need, or that they didn’t know of support groups for my particular type of cancer. So I turned to online support groups.

I’ve heard from other people with cancer that they’d had a negative experience looking for information online, particularly with groups or individuals who are trying to peddle unproven alternative treatments.

I found it useful go to some of the bigger evidence-based websites — Cancer Council Australia, the American Cancer Society, MacMillan Cancer Support and TC-Cancer.com.

These organisations have good quality information, online cancer forums, in-person support groups and sometimes telephone support.

People often want to help — tell them how

My experience is that when people hear you have cancer, they usually want to help. Often, however, they don’t know how.

Some people disappeared from my life, or didn’t speak about the cancer at all. While I understood why they might do this, I didn’t find this helpful at all. It also didn’t help when they said things like, “everything will be just fine, don’t worry”, or share with you that someone they knew had died as a result of their cancer.

What helped me was when people treated me as they normally would. They talked off the cuff, said whatever sprung to mind — business as usual. I loved it when people visited just to talk. It made me feel like they were listening, that they really heard what I had to say, and that they cared.

My wife and I found that there were lots of practical ways our friends and family could help us during my diagnosis and treatment, such as by offering babysitting, meal preparation, help with housework or coming with me to oncology appointments.

My experience is that carers will be the ones who have to carry the load as you go through treatment and recovery. They also need practical help and emotional support. It’s a difficult time for all of you, and you don’t have to do it all yourselves.

Do the things that make you feel good

Good nutrition and regular exercise have really helped me in my recovery, and with managing my mental health.

During treatment and afterwards I had a routine where I went for a walk every night, even when I felt very low and tired, and couldn’t go very far. It gave me more energy and made me feel better, made me reconnect with the world around me.

Find what it is that makes you feel good, and do it, even when you are feeling unwell.

Try and manage your worries

When I had cancer, even a small worry could turn into a big worry — if, for example, I had a headache, I would wonder, “is this the cancer coming back?”.

My belief is that worry often comes from uncertainly. If you can identify the source of the uncertainty, more often than not you can start to take some control over the worry.

If my worries are really taking over, I take five minutes to write down all the things that are concerning me right now, without editing or culling. I then look at them and break these up into those that I can do something about, and those I can’t change.

I might then take a specific worry (such as my concern that the latest tests I had will show that the cancer has returned). I write down what every foreseeable outcome that could stem from such as event might be.

I found this to be a very practical way of putting my concerns on the page so that I could get a bit more control over them and look at them more rationally.

The most important thing I’ve learnt through this journey is that no one is as invested in your own wellbeing as you are yourself.

To have some measure of control over what will likely be the most uncertain and challenging time of your life, you need to take advice from your treatment team, research your own information and take advantage of any support services — for yourself and your family.