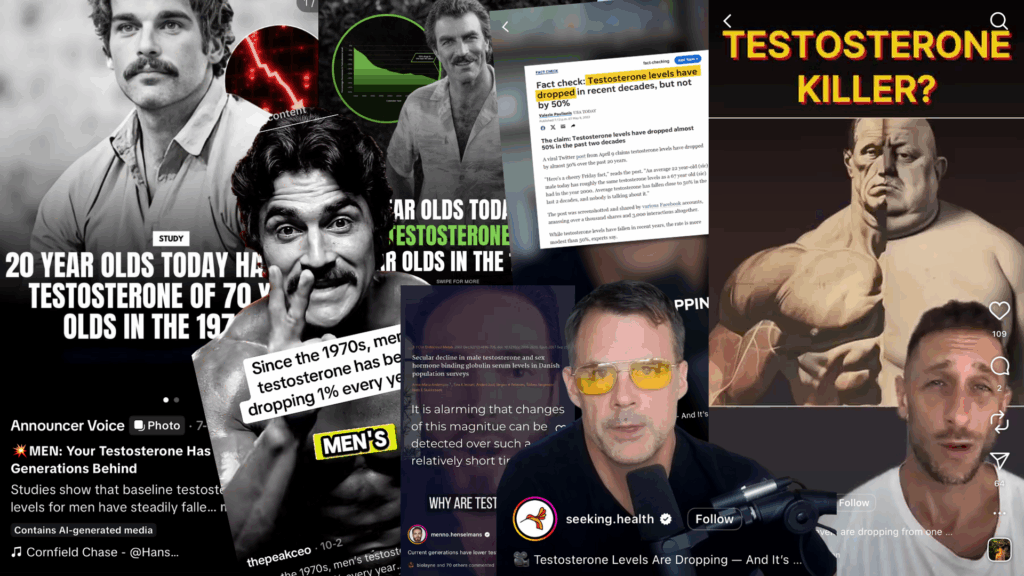

Whether it’s to justify testosterone injections, encourage us to tan our balls or bemoan the pathetic state of modern men, claiming that men’s testosterone levels are lower now than they were back in the day is pretty common. Are these claims true? If so, what is the cause and what can we do about it?

What does the research say?

The idea that there might be a population-level decrease in testosterone over time was raised about 20 years ago by a study of three groups of men. They had their testosterone levels measured in either 1987-9, 1995-7 or 2002-4. Total testosterone levels declined from a median of 501 ng/dl (17.4 nmol/l) in 1987-9, to 435 ng/dl (15.1 nmol/l) in 1995-7, and 391 ng/dl (13.6 nmol/l) in 2002-4. Since that time, there have been at least 10 other studies showing similar decreases in population testosterone levels.

What is causing this drop in testosterone levels?

None of these studies tells us the cause (or causes) for this decrease in testosterone levels. There are a lot of things that are known to affect men’s testosterone levels, and many have changed in prevalence or severity over the time period that testosterone levels have been falling (since the 1970s). Things like diet, physical activity levels, alcohol and other drugs, sleep, environmental exposures, and chronic diseases like high blood pressure, diabetes, overweight and obesity and stress can all affect testosterone levels and have all changed during the last 50 years.

Some of the studies that show a fall in testosterone have tried to account for some of the possible causes. These use statistical techniques to ‘adjust’ for differences that can affect testosterone without being the main thing the researchers are looking at. After these sorts of adjustments, some studies show that the decline in testosterone levels disappears, and others show that it remains. The different outcomes from these adjustments are probably because they adjust for different things (some studies don’t measure important confounding factors like specific health conditions), and because these types of adjustments are not perfect.

Here’s an example of why statistical adjustments might not work: There’s a well-established negative relationship between body fat and testosterone (the higher your body fat, the lower your testosterone), so most studies try to deal with that by adjusting for body mass index (BMI). The problem is, BMI isn’t a measure of body fat. BMI is increased by weight gain, regardless of whether the increased weight is due to body fat or muscle (lean mass). Fat mass and lean mass have opposite effects on testosterone (the higher your lean mass the higher your testosterone level), so adjustment for BMI is inaccurate.

The studies that show a decrease in testosterone over time do the best they can at using data that were usually collected for another reason to answer an important question. There might be other studies, using other data sets and similar analysis, that have also looked at this question and found that there is no change over time, but they are less likely to be published so we don’t know about them. The reason these same types of studies keep getting done is because we still aren’t confident with our answer to the question. What we really need is a properly designed study, but it would take decades to perform and cost heaps of money, so no one is going to do it.

The main takeaway

I think that the decline in testosterone levels over the past 50 years is probably due to increasing rates of chronic disease, especially obesity and diabetes. We know from longitudinal studies of individual men that those who stay healthy as they age don’t have a fall in testosterone. It makes sense that this effect of poor health would work on a population level too.

There’s plenty of speculation that endocrine-disrupting chemicals, microplastics or other pollutants might be contributing to the decline in testosterone, but there’s not a lot of good-quality evidence to support those claims. The evidence for the effect of poor diet, lack of exercise and increasing rates of disease on testosterone is much more compelling, and these are factors that are generally within individuals’ control.