At 16, Owen thought the pain and bleeding he had when going to the bathroom would just go away. Instead, it marked the beginning of years of hospital stays, brutal treatments and a surgery that would change his body — and his life — forever. Owen shares his experience going from critically ill to an elite endurance athlete, rebuilding not just his health but his identity.

When I started experiencing symptoms, it showed up as a bit of pain when I’d pass my bowel motions and then I’d have a bit of blood or mucus. It’s a bit of a taboo thing to talk about. I was 16, I wasn’t going to turn around to my mates and discuss it. I just waited to see if it would go away but it gradually got a lot worse.

After about three months, I went to our family GP. I’ve seen him my whole life. He was just like, ‘pants down, we’ll have a look’. And barely did anything else. He said it was internal haemorrhoids and sent me on my way. I was at the end of year 10 and in the following six months, I deteriorated so fast. I’m 6’1 and I weighed 56 kilograms. There was nothing left of me. I was malnourished. It finally got so bad that I went to the ER and that’s when I was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis, which is an autoimmune disease that causes your immune system to attack your colon. It had started near my rectum, where symptoms are the worst and developed into 300 ulcers throughout my entire colon. Anything I would eat would tear these ulcers open and fill my colon with blood.

Over the next two years, it was trial and error with treatment

The standard path for everyone with severe inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is taking prednisone, which is an oral steroid that helps lower inflammation for a different medication to help you. But the side effects of steroids can be big. I was 16, 17, 18 years old. I’ve got formal, birthday parties, graduation, a lot of times where photos are so important. I’d come out of the hospital gaunt and skinny, and within two weeks, I’d put 20 kilos on. I felt physically disgusting and mentally, I just forgot who I was, I really struggled with that. All I was thinking about was who I was before I got sick.

It felt unfair. I was so upset. ‘Why me?’ — all those questions come up. But looking back, it’s because I hadn’t established who I was. I was always comparing myself to someone who was completely healthy. And the reality of it is it’s a chronic illness. There will never be a time when you’re that person again. The time it takes to come to terms with that is scary because anything can happen in that time.

“That struggle came out in so many bad habits and really bad attitudes. Doing things that made it worse for my body. I was in full destruction mode.”

But I was lucky enough to have people around me who really wanted to help me. My year 11 coordinator always vouched for me. She had extra patience for me and believed in me. Our last year was during the COVID-19 lockdowns, which was great for me, because school was online and I was so sick. I went from nearly getting expelled to getting a 90 ATAR because I was just able to just knuckle down at home. I had a great group of friends but it was hard to talk about. No one was really able to understand, but I didn’t even understand and it was happening to me.

After four years of different treatments we started to discuss the option of an ileostomy. This is when the end of the small intestine is connected to an opening in the abdomen. An ostomy bag is then attached to the end of the stoma to collect your waste. I booked a three-month Europe trip with my best mate and headed there with a bag full of medication. At that point, I would have happily ended my life in Europe, I thought surgery was the end of my life anyway. I didn’t want to plan to take my own life, but I thought about it in a way where I would have partied to that point. It could have been seen as an accident. I wasn’t scared of losing my life.

When I came home I was a shambles

I’d been drinking and doing all these things on steroids so I’d developed shingles, I’d had insomnia and shooting pains like electricity crawling through my skin, so many issues. So I was just like, my hands are up I’m ready for surgery. Luckily, the day I went in not long after being back. They started operating on me and realised my appendix had burst and that would have killed me. I was in so much pain already, for years, that I hadn’t realised.

I was in that surgery for nine hours and in the ICU for two days. It was traumatising. After nine days I was released to go home but after three days I had deteriorated badly. I was in immense pain and going in and out of consciousness. In the middle of the night my mum and my girlfriend rushed me to the hospital. My stoma had turned black from an obstruction. I was straight into another operation for six hours.

“I’m not religious, but when I got onto the operating table, I was like, ‘please God, if I survive this, I will take care of my health’.”

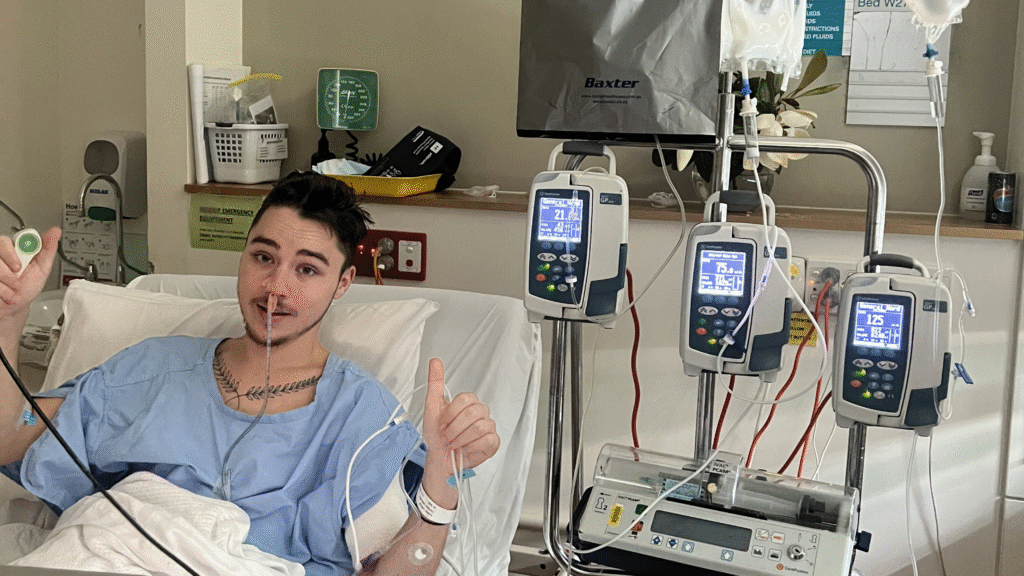

I cannot ever bring myself to that level ever again. I woke up with a nasogastric tube, hooked up to an absolute Christmas tree of cords and machines and I stayed in hospital for a month after that. That experience really shaped who I am now.

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t have nights where I have my mum there going, ‘I want it to end’. It felt like prison. I couldn’t walk. I hadn’t felt wind on my face in weeks, or opened my own door, or smelt a new smell that wasn’t some sort of anaesthetic. But it shaped me for all the right reasons in a way, because it showed how resilient the human body was and how much I should value that. When I got released, I really turned a page.

I had a new opportunity to get at life

It took around two months and then it was like flicking a light switch. It was insane. I just felt so good. And by so good, I mean I could walk 500 metres outside. I was really excited to get healthy. So I signed up for a sprint triathlon four months afterwards. My mum is a marathon runner and I always ran with her because I loved to play soccer. But when I got sick I turned to partying rather than sport. I came back to running because it was so accessible; all I had to do was put my shoes on.

At first, I was walking. Just from light pole to light pole. I had no pressure or expectations. All I wanted was to feel strong again. I’d didn’t own a bike, I’d never swam with a stoma until race day. After everything that had happened, I wasn’t going to restrict my life just because of my bag.

“It had allowed me to live. After the triathlon I felt incredible. I was like, I can do these things.”

And I’ve done plenty of things since. My girlfriend and I summited Mount Kinabalu, the highest peak in Malaysia, just before my first ever marathon. Last year I did the Ultra Trail Australia Major, one of the biggest races in the southern hemisphere for trail running — 100 kilometres through the Blue Mountains. That result got me picked for the Shokz Australian team to go race at one of the most prestigious invitational races in the world, the MCC by ultra-trail of Mont Blanc. We got to do the opening race for it, which is 50km, from Switzerland to France. Around 3,500 meters of elevation, where I ended up finishing as the first Australian.

I went on to achieve a huge highlight, the Great Southern Endurance Run in Mount Hotham. I was invited by Mick Marshall, who has a bilateral lower limb and neurological (CRPS) disability and has been relearning to walk after shattering his legs in a fall. He now races with crutches. He built a relay team to be the first adaptive team to finish it, with myself and Dale Pierce, who’s blind and did his eight kilometres with no guide, just a cane. We went on to become the first-ever adaptive athlete team to complete the Great Southern Endurance Run.

The week after, I did the Ultra Trail Kosciusko, which was 104 kilometres and smashed my PB by four hours. My grandfather had recently passed away and weeks before when I was in France for my race, he told me he couldn’t do it anymore. When I heard him say that, a man who is spoken about with such high honour and regard by everyone who knows him, I swore to never say I couldnt do it, till I’m on my deathbed. I had a fire in my belly. As I progress in this sport, I really want to continue to bring in awareness to try to create a category for adaptive athletes.

There was no one to show me what was possible

Barely anyone is showing themselves training with a stoma bag. My social media page came about because that’s what I wanted. Someone I could talk to and relate to about living with a stoma. It took a lot of time and a lot of balls to do. But now on socials I’ve got plenty of content with my shirt off, bag out. I don’t struggle with it as much anymore. When it came to living with my bag, straight away I bit the bullet and was just like, don’t try to hide it because it’s going to create habits that you’re going to regret later on. I was lucky enough to have a girlfriend from the jump. Realistically, people don’t really care, but I think the beginning can be tough from an intimacy point of view.

I’ve been able to develop myself as a man, through all these hard things. I’ve actually become a nicer person for it. A better friend and partner. I’ve become a more patient person. I’ve become more understanding. My perspective on things has changed and broadened. I’m just happy that I’m feeling the wind on my face. When you’re really sick you feel fragile, you feel weak, you’re exposed to a lot of vulnerable situations where people are poking and prodding and you’re seen at your worst.

“I’m super proud of the person I am now because of what I’ve been through.”

It’s easy to just go f*** everyone, my body tried to kill me so why would I be scared of any of you. I felt like that when I was younger but that didn’t make me more of a man. How I am now, that’s good masculinity. I’m still here, I’m still loving, caring and empathetic.

My advice to others who are where I’ve been is to take it slow. Shed all expectations and learn to love yourself and the smallest of wins. When you’re rebuilding yourself — whether that’s from chronic illness or mental health challenges — you can’t just take five steps in one go. You’ll crumble and fall further back. Baby steps allow the big steps. Find the things you love and love yourself.

You can follow Owen on Instagram here and learn more about ulcerative colitis through Crohn’s and Colitis Australia, who provide support services, advice and encouragement to people with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).