There has always been conflicting advice on whether a GP should order PSA (prostate specific antigen) testing for their patients, due to the ambiguity around the potential benefits and risks of the test. However, over the past two years, the use of PSA testing has evolved with better outcomes for the patient.

PSA testing benefits

Like any screening test, the rationale for PSA testing is to detect harmful types of prostate cancer early, while they are still localised and therefore likely to be curable. The most rigorously conducted clinical trials show that PSA testing does catch prostate cancer early, and that, with curative treatment, rates of illness and death from the cancer are reduced. Because of this, PSA tests were naturally favoured.

PSA testing risks

In the past, an elevated PSA result led straight to a transrectal ultrasound guided (TRUS) prostate biopsy. This procedure was often performed without sedation, so the process could be painful and embarrassing for the patient.

When harmless low-grade prostate cancer was detected by TRUS biopsy, the patient was often then subjected to aggressive treatment in case a more aggressive cancer appeared. This treatment can often have side effects with major impacts on quality of life, such as problems with urinating or erections.

With a TRUS biopsy, there was also a small but significant risk of severe infection (sepsis) if bacteria from the bowel was accidentally transferred when the needle passed through the bowel wall into the prostate. In addition, as these biopsies were taken randomly from around the prostate gland, if aggressive cancer were present it could be missed.

Most of the time the biopsy would find no cancer, meaning cancer was missed or that the PSA was elevated for another reason, such as benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

Evolution of PSA use

Measures have been taken in recent years to reduce patient harm when it comes to PSA testing.

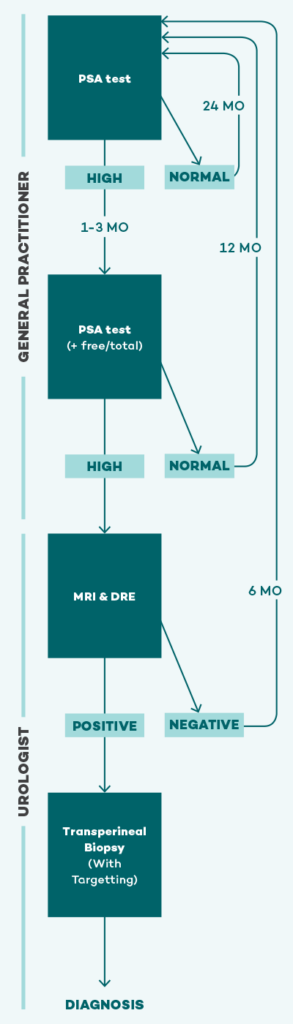

Now, a single elevated PSA measurement is no longer immediately followed by a biopsy. Instead, a repeat PSA test (preferably including measurement of the free/total PSA ratio) is taken one to three months after the first test.

It is well-recognised that PSA will naturally fluctuate to some extent within individuals, so the second PSA is often normal, precluding the need for further evaluation.

If the second PSA measurement is high, the free/total ratio can help determine the chance it is due to benign prostatic hyperplasia (free/total PSA >25%) or cancer. If the subsequent PSA remains elevated, and the free/total ratio is abnormal, the next step is to refer to a Urologist, who will order the non-invasive test of a multiparametric prostate MRI.

Prostate MRI

Prostate MRI has only last year become standard of care in the evaluation of men with an elevated PSA. If the MRI is negative, a biopsy can usually be avoided altogether. On the other hand, if the MRI does show a lesion, this lesion can then be precisely targeted at subsequent biopsy, maximising diagnostic accuracy. Finally, MRI typically does not detect harmless low-grade prostate cancer — which is exactly the type we do not want to find. By avoiding a biopsy when no lesion is seen on MRI, we therefore avoid unnecessarily diagnosing most of the harmless types of prostate cancer, and the chance of having them unnecessarily treated.

If a lesion is found on the MRI and a targeted biopsy is performed, this is now more often done via the skin between the scrotum and anus (perineum) under general or local anaesthetic, rather than through the rectum, thereby avoiding rectal bacteria. Numerous studies show a zero or near-zero risk of infection using this technique. Prostate biopsy sepsis has therefore been all but eradicated.

Occasionally, harmless low-grade prostate cancers are still detected at biopsy. The good news is that these can almost always be managed by monitoring (sometimes known as active surveillance) rather than by any treatment, thereby again avoiding the potential significant side effects of treatment.

For GPs, knowing the benefits and risks of PSA testing is imperative. For male patients aged 50-70 years, when prostate cancer typically first arises, GPs must start the conversation of PSA testing and not simply wait for patients to present with symptoms.

For more detailed recommendations, including for men with a family history of prostate cancer, please see the RACGP-endorsed clinical practice guidelines on PSA testing and early management of test-detected prostate cancer.