Every military member experiences discharge differently, depending on a bunch of individual factors. I’ve watched mates thrive after discharge and never look back, and I’ve also had mates spiral downward with mental health issues and even suicide. Most, myself included, find ourselves somewhere in between riding an emotional rollercoaster for a while before eventually finding our feet as civilians. Most veterans experience high levels of stress during their transition to civilian life even if they don’t have any post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) issues.

Here are a handful of things I hadn’t anticipated when I was discharged but would have been useful to know at the time to smooth out the ride a little.

1. You may not see the cliff coming

I was lucky enough to leave the military on my own terms and had only considered the positives of being a civilian again, such as spending more time at home with my family and an increased wage as a civilian doctor. I hadn’t anticipated discharge to be a struggle, so hadn’t felt the need to engage in any of the voluntary discharge planning services offered that might have helped me psychologically prepare for the transition.

There was a “honeymoon period” that lasted for almost a year when it felt like I was on leave from the military. The reality of my discharge hadn’t sunk in. It was only then that the cracks started to appear.

2. You might lose your identity (or a big part of it)

On reflection, the main struggle I had after discharge was working out who I was as a civilian.

In hindsight, I recognise my own ‘identity fusion’; my personal identity was fused with my work role as an army doctor. This was great when I was still on the job, and it was going well, but left me lost when I was discharged.

3. You will lose your tribe

Humans are hardwired for connection and to be part of a tribe. This makes sense from an evolutionary perspective when isolation could quite literally be life-threatening. In many ways, the military is the ultimate tribe. It brings members together in tight-knit groups that share rich bonding experiences, potentially including combat and the loss of teammates.

Discharge from the military can feel like an abandonment of your tribe and the loss of the support of those who you feel truly know and understand you. It is natural to grieve this loss and feel a sense of isolation.

4. You might feel lonely

During my transition to civilian life, a quote from the psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung resonated deeply:

“Loneliness does not come from having no people about one, but from being unable to communicate the things that seem important to oneself, or from holding certain views which others find inadmissible.”

Having been immersed in military culture for many years, when I first found myself back at civilian gatherings, I felt like a fish out of water.

It seemed near impossible to relate to those around me, and I felt incredibly lonely.

5. Civilian life might seem boring

It’s human nature to experience ‘hedonic adaptation, which is the tendency to recalibrate to new life circumstances. Military members undergo a selection process and are generally high-functioning individuals. Once in the military, members are regularly exposed to stressful situations like extreme heat, smoke, sleep disturbance, strenuous bouts of physical exertion and potential injury, even if they’re not deployed.

Members get used to working under extreme levels of occupational stress, with high-functioning, motivated people. When they return to civilian life, the lower level of occupational stress and a variety of personalities in civilian society can take some adjustment.

6. You might lose your sense of purpose, motivation, and resilience

A career in the military can provide a great sense of purpose, which helps maintain motivation toward self-improvement and feelings of contribution. Psychologist Abraham Maslow offers a model of human motivation that encapsulates much of what a military career offers. Known as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the model’s base is formed by physiological and safety needs, things like food, water, housing etc.

My experience piqued a deep personal interest in the concept of resilience. Ultimately, this led to co-authoring the book The Resilience Shield, which describes our dynamic, multifactorial, and modifiable model of resilience and provides a roadmap for rebuilding and maintaining robust resilience after taking a hit, such as military discharge.

7. There is a pathway forward

Although the transition from the military can be a tough adjustment, the good news is that there’s a pathway forward. Just as it takes years to develop a military identity, it takes years to develop a new civilian identity. Keeping in touch with military mates can be a great way to stay connected to your past, but equally important is forming a new tribe of civilian friends to move forward with. While it may be hard to relate at first, if you look carefully, you will find shared values and interests to connect you to new tribe members.

Being kind to yourself throughout the transition to civilian life is imperative. Sometimes it’s healthy to ease up on a few of the values that served you well in the military but aren’t as relevant as a civilian. While it might have been a matter of life and death to get to an extraction point on time, does it really matter that you’re running five minutes late for dinner with friends?

Take your time to adjust back to the pace of civilian life and lean on those close to you for support.

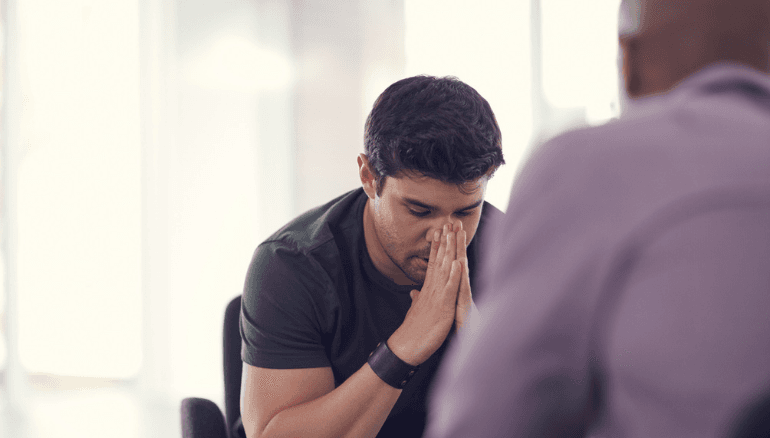

If you’re struggling, it’s time to let go of the suspicion of psychologists that is typical in the military and go and see one. Psychologists are specialists with the tools to help you heal any psychological wounds and move towards a self-actualised civilian version of yourself. Actively build your resilience, search for a new purpose, and when you find it, the motivation will come to power forward. You did it once in the military, so you can certainly do it again!