When to perform a genital examination

When to refer

| Condition | Referral time frame |

|---|---|

| Suspected testicular torsion | Immediate |

| Inguinal hernia – neonate | 1 week |

| Inguinal hernia – infant | 2–4 weeks |

| Inguinal hernia – child | 1–3 months |

| Phimosis – pathological | 1–3 months |

| Undescended testis | 3 months |

| Umbilical hernia | After 3 years of age |

| Phimosis – physiological | After 7 years of age |

Table adapted from Teague & King, 2015. Paediatric surgery for the busy GP – Getting the referral right. Aust Fam Physician

How to conduct a genital examination of a young male

If referral to another specialist is required, explain why and what might be involved.

Undescended testis

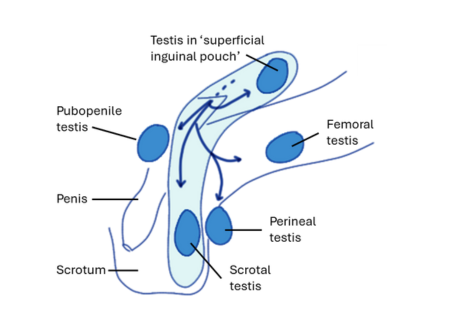

Presentation usually occurs after someone notices the scrotum appears empty. It is useful to know, by asking a parent or carer, the location of the testes at birth or during infancy (Figure 1).

Testes that were previously fully descended, but are now unable to be palpated into the scrotum and rest there, may be ascending.

It should be possible to visualize the full scrotum and its contents (or absence of the testes in a flat scrotum) with the patient lying or standing. Alternatively, having a small boy squat or an older boy sit with his knees held to his chest, will usually reveal the testes in the scrotum.

The testis is a mobile organ and will not sit constantly in the scrotum. They are particularly mobile in toddlers and young children.

This is because the testis remains relatively small prior to puberty, and the cremasteric muscle which it is attached to is particularly active.

Undescended testes can usually be palpated by gently rolling the flattened fingertips of one hand over the inguinal region.

The testis is usually felt as a mobile, spherical structure, located between the muscles of the abdominal wall and subcutaneous fat. Normal testicular volume between ages 6 months to 10 years is 1-2 ml (similar in size to the glans penis).

By applying gentle pressure slightly laterally and above the testis, it should be possible to ‘milk it’ towards the scrotum.

Undescended testes cannot be manipulated into the scrotum and may be completely impalpable or present in an ectopic location.

It may be possible to palpate the spermatic cord of an ectopic testis, as it emerges from the external inguinal ring and follow it to the testis.

An ectopic testis may be lateral to the scrotum, in the thigh (femoral testis), medial to the external ring (pubopenile testis) or behind the scrotum (perineal testis) but these locations are rare.

Absence of a testis may be suggested by compensatory hypertrophy of the contralateral testis (i.e. but a small ipsilateral testis may still be present in the abdomen).

Retractile testes may be visible in the scrotum by applying upward traction on the pubic skin to pull the scrotum up.

Acute scrotal pain

Infants usually present with scrotal redness, swelling or induration, and may be crying, distressed, vomiting or febrile. Older boys and adolescents may present with pain in the iliac fossa, flank or loin, usually with accompanying scrotal pain and tenderness.

Examination of acute scrotal pain identifies if testicular torsion remains a differential diagnosis (which is often the case) and that being the case urgent surgical consultation is required and the child should remain fasted. Doppler ultrasound examination of the scrotum may be useful but should not delay intervention.

The mumps virus tends not to target the immature testes, so acute scrotal pain in children is rarely caused by mumps.

Testicular torsion occurs most frequently in peripubertal children (twisting occurs inside the tunica vaginalis) but can occur at any age. In the perinatal period torsion may also occur through different mechanisms (usually the tunica vaginalis and its contents twist).

In both testicular torsion and torsion of a testicular appendage, a hydrocele around the testis may be present.

If testicular torsion is the cause, redness and swelling occur in the hemiscrotum with the affected testis. The affected testis may be located high in the scrotum because of the spermatic cord shortening as it twists (Figure 2).

The pain associated with testicular torsion may subside once infarction has occurred. Testicular viability is significantly threatened if the twisted testis is not corrected surgically within 6 hours of the onset of pain.

Time from onset of symptoms to presentation to a health professional represents an ongoing public health challenge in these children.

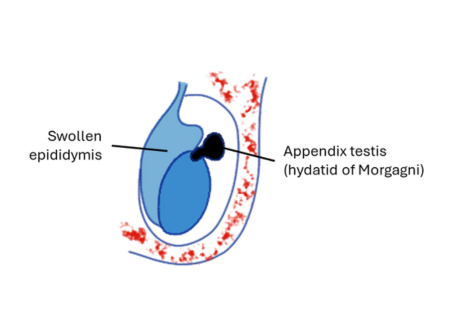

Torsion of the appendix testis (hydatid of Morgagni) may be revealed by a blue/black spot, seen through the scrotum near the upper pole of the testis, if inflammation is minimal and if torsion has produced haemorrhage in the cyst (Figure 3).

However, the “blue dot sign” may be easily confused with superficial or deep venous structures.

In the absence of haemorrhage, torsion of the appendix testis will not be visually apparent. A cyst the size of a pea will be palpable near the upper pole of the testis. The cyst will be very painful to touch but the testis itself will not be tender.

Epididymo-orchitis is uncommon in children but may occur secondary to urinary tract malformations and infections in infants, and it becomes increasingly common as age increases throughout adolescence.

Signs of epididymitis are non-specific. The spermatic cord may be swollen and sore to touch. Certainty of diagnosis requires surgical investigation.

Urine MC&S may indicate the presence of UTI/epididymo-orchitis but a urine test should not delay urgent surgical exploration where testicular torsion remains in the differential diagnosis.

Boys with a confirmed episode of epididymo-orchitis should subsequently undergo a renal tract US to identify any congenital urinary tract abnormalities.

Idiopathic scrotal oedema is most likely to be due to allergic-type inflammation. It appears as a superficial wheal. It is characterized by an inflammatory process that is not isolated to a hemiscrotum, and may involve both sides of the scrotum, the penis, perineum and/or thigh.

Manipulation of the testes should cause little pain, and it should be possible to displace them from the scrotum into the superficial inguinal pouch, and observe their normal size and consistency.

Painless, swollen scrotum

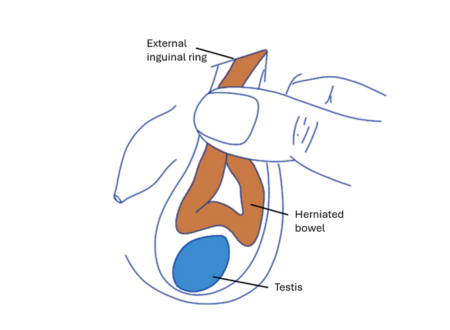

Painless scrotal swelling is most commonly caused by hydrocele or indirect inguinal hernia (inguino-scrotal hernia). Less common causes are varicocele, haematocele or testicular cancer.

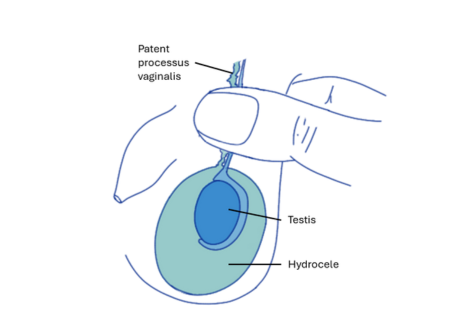

Hydrocele (Figure 4) results from passage of peritoneal fluid through a narrow patent processus vaginalis into the scrotum.

Swelling may increase over the course of the day, when activity causes increased intraperitoneal pressure, and resolve during the night, as fluid is removed by tissue reabsorption. Swelling is also typically worse during the course of a viral illness.

Inguino-scrotal hernia (Figure 4) causing scrotal swelling are palpable in the neck of the scrotum and transilluminate only dimly. Unlike a hydrocele, an inguinal hernia can be reduced by taxis (manual compression).

Varicocele often presents no symptoms but there may be mild discomfort or a heavy ‘dragging’ sensation. Varicocele is almost always left-sided and feels like a ‘bag of worms’ when palpated.

It may be absent when lying down and only palpable or visible when standing or when intra-abdominal pressure is raised (e.g., coughing, straining).

Ruling out an abdominal mass is important (either clinically and/or radiologically) particularly in right-sided varicoceles.

Haematocele, usually caused by direct trauma, is uncommon in children but presents with bruising of the scrotum. In the absence of a clear, plausible and repeated history consistent with the injury, non-accidental injury needs to be considered.

Testicular cancer can present as an enlarged, irregularly shaped testis surrounded by a secondary hydrocele. For this reason, a normal testis should always be confirmed by palpation when a hydrocele is diagnosed.

Lump in the groin

A groin lump caused by an inguinal hernia will be located near to the external ring of the inguinal canal (along the inguinal ligament, between the pubic tubercle and anterior superior iliac spine).

A hernia can be distinguished from an encysted hydrocele (which may present near the external ring) by applying traction to the testis: a hydrocele will move down but a hernia will not.

If an inguinal hernia cannot be reduced, it should be considered strangulated and treated urgently.

The absence of a demonstrable hernia is insufficient to rule one out, if a clear and reliable history is provided by a parent or carer (with clinical photographs of a bulge present at the external ring).

Boys with inguinal hernia should be immediately referred to a paediatric surgeon.

Information and images (redrawn) based on

Hutson & Beasley, 2013. Inguinoscrotal Lesions (Chapter 4), The Surgical Examination of Children. Springer DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-29814-1

References

EAU Guidelines, presented at the EAU Annual Congress Milan 2023

Clinical review

A/Prof Kiarash Taghavi FRACP(Paed Surg) MBChB PGDipSurgAnat DipPaeds GCertClinTeach CHIA, Monash Children’s Hospital and Monash University; March 2024